Opinion: Why did Lukashenko allow the opposition into Parliament?

BelarusFeed

27 September 2016, 18:03

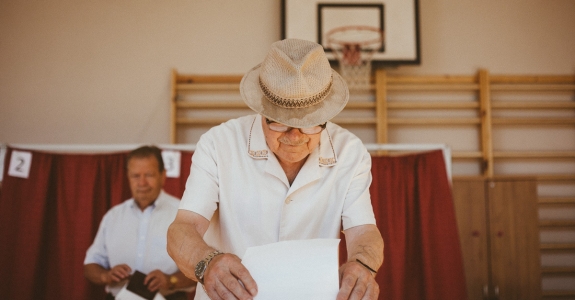

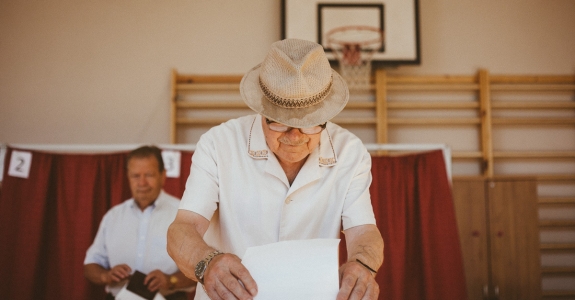

With almost two weeks after the parliamentary elections in Belarus and the fuss about the results a little down, it may be a good time to reflect on what we have witnessed. Artyom Shraibman, a political contributor at Belarusian news portal TUT.BY, is looking into the matter.

With almost two weeks after the parliamentary elections in Belarus and the fuss about the results a little down, it may be a good time to reflect on what we have witnessed. Artyom Shraibman, a political contributor at Belarusian news portal TUT.BY, is looking into the matter.

In light of Minsk’s strict control over the electoral process, the election of two oppositionists to Belarusian parliament suggests that President Alexander Lukashenko is looking to improve relations with the West. How far will he go?

On September 11, Elena Anisim and Anna Kanopatskaya became the first oppositionists to be elected to Belarusian parliament in twenty years. For the first time, some in the West are starting to refer to the parliament as an “elected” body, and Anisim’s and Kanopatskaya’s victories seem likely to be the catalyst for increased cooperation between Belarus and the West in the coming years.

Despite the parliament’s new look, however, the Belarusian authorities’ grip remains as strong as ever: election observers noted that turnout numbers reported by district voting commissions were significantly inflated, and it would be naive to think that other elements of the voting were not tampered with as well. Belarus’s electoral procedures haven’t changed at all, and it would be wrong to see Anisim’s and Kanopatskaya’s victories as indicative of any kind of perestroika, agitation for liberalization among elites, or even a loosening of the reigns in individual voting districts.

The decision to allow the opposition into parliament was made consciously in Minsk as part of a year-long effort to improve relations with the West. It was an intentional introduction of dissonance into the familiar calm of Belarusian politics. Although the opposition received no meaningful leverage other than the ability to protest slightly louder, it’s a big step for Lukashenko.

He wouldn’t have taken such a step without encouragement: someone must have convinced the president that concessions of this magnitude were necessary. This was likely the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which likes to maintain Belarus’s foreign policy balancing act, keeping Minsk on the tightrope strung between Moscow and Brussels.

The first sign of change came from Lukashenko, who spoke at a voting station on the day of the elections. Responding to a well-placed question from a Russian journalist about Western sanctions, the president said, in an uncharacteristically soft manner, that Minsk has always wanted all sanctions to be lifted. And if the West’s requirements are achievable, he continued, “Why should we be stubborn?” He also announced a forthcoming resolution to the issue of the Belarusian and American ambassadors, who were recalled from each other’s capitals eight years ago.

Clearly, Belarusian authorities wanted to make sure that their signal was received loud and clear in the West.

It seems to have been, at least initially. Observers from the OSCE announced that the distance between the current situation and truly democratic elections in Belarus is as far as between the earth and the moon, but for the first time referred to the parliament as “elected.” One of the leaders of the OSCE mission went as far as to call the admission of members of the opposition to parliament a “historic moment.”

Early statements from Brussels and Washington echoed the OSCE’s: things aren’t exactly democratic, they said, but there has been some progress that we want to see continue.

Even before the elections, Minsk, Brussels, and Washington were making efforts to improve relations, though the relationship was—and is—burdened by previous failed attempts at rapprochement: efforts to improve relations between 2008 and 2010 ended when Belarusian authorities dispersed a mass protest after the 2010 presidential elections and imprisoned its leaders.

It’s certainly hard for the West to turn a blind eye to Lukashenko’s authoritarianism, just as it’s hard for Lukashenko to ignore pressure from Moscow. Nobody wants to accidentally give Moscow a reason to ignite a second “Russian Spring.”

Each side is, as before, carefully assessing the other, afraid to do too much. Such a sluggish diplomatic process demands constant stimuli, the first of which came last year, with Minsk’s release of six political prisoners. Sanctions were soon suspended. Next came peaceful, repression-less presidential elections; the EU abolished its sanctions shortly thereafter. Then came this year’s parliamentary elections.

The path toward a closer relationship between the United States and Belarus is now more or less clear: Washington and Minsk will discuss lifting the sanctions and reinstating the ambassadors.

The EU, for its part, can offer Belarus several things: Minsk and Brussels have been negotiating a faciltation of the visa regime for the past three years, and now may be the time to hammer out any remaining technical issues (although a visa-free relationship is a long way off).

There is also the signing of a partnership agreement, which Brussels has negotiated with all the members of the Commonwealth of Independent States except Belarus and Turkmenistan. Minsk has called for negotiations on this agreement for a long time, and now may be the time for the EU to bring Belarus into the fold.

Things get trickier when it comes to money. Restrictions keeping the European Investment Bank (EIB) from working in Belarus and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) from working with the Belorussian state sector have already been lifted. Now it’s up to Minsk to propose projects that interest the EIB and the EBRD. Issues related to trade and investment will certainly be essential to any budding relationship between the EU and Belarus. Brussels can do several things on this front, including bringing Belarus back into the Global System of Trade Preferences and starting new investment forums.

Finally, the European Union can increase the scale of its development assistance to Belarus, which it doubled at the start of this year. But even in the best-case scenario, we’re talking about only a few hundred million euros spread out over many years. Minsk will be pleased, but the country’s economy will hardly feel the difference.

Seen from above, Brussels has a number of steps it can take, but none of them are game changers. After Lukashenko’s gesture in the parliamentary elections, European bureaucrats responsible for relations with Minsk will most likely pause to figure out what carrots the EU can offer Belarus next. They will have to choose carefully, however, because there are limits to partnership, and putting everything on the table at the same time would be imprudent.

27 September 2016, 18:03

In light of Minsk’s strict control over the electoral process, the election of two oppositionists to Belarusian parliament suggests that President Alexander Lukashenko is looking to improve relations with the West. How far will he go?

On September 11, Elena Anisim and Anna Kanopatskaya became the first oppositionists to be elected to Belarusian parliament in twenty years. For the first time, some in the West are starting to refer to the parliament as an “elected” body, and Anisim’s and Kanopatskaya’s victories seem likely to be the catalyst for increased cooperation between Belarus and the West in the coming years.

Despite the parliament’s new look, however, the Belarusian authorities’ grip remains as strong as ever: election observers noted that turnout numbers reported by district voting commissions were significantly inflated, and it would be naive to think that other elements of the voting were not tampered with as well. Belarus’s electoral procedures haven’t changed at all, and it would be wrong to see Anisim’s and Kanopatskaya’s victories as indicative of any kind of perestroika, agitation for liberalization among elites, or even a loosening of the reigns in individual voting districts.

The decision to allow the opposition into parliament was made consciously in Minsk as part of a year-long effort to improve relations with the West. It was an intentional introduction of dissonance into the familiar calm of Belarusian politics. Although the opposition received no meaningful leverage other than the ability to protest slightly louder, it’s a big step for Lukashenko.

He wouldn’t have taken such a step without encouragement: someone must have convinced the president that concessions of this magnitude were necessary. This was likely the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which likes to maintain Belarus’s foreign policy balancing act, keeping Minsk on the tightrope strung between Moscow and Brussels.

The first sign of change came from Lukashenko, who spoke at a voting station on the day of the elections. Responding to a well-placed question from a Russian journalist about Western sanctions, the president said, in an uncharacteristically soft manner, that Minsk has always wanted all sanctions to be lifted. And if the West’s requirements are achievable, he continued, “Why should we be stubborn?” He also announced a forthcoming resolution to the issue of the Belarusian and American ambassadors, who were recalled from each other’s capitals eight years ago.

Clearly, Belarusian authorities wanted to make sure that their signal was received loud and clear in the West.

It seems to have been, at least initially. Observers from the OSCE announced that the distance between the current situation and truly democratic elections in Belarus is as far as between the earth and the moon, but for the first time referred to the parliament as “elected.” One of the leaders of the OSCE mission went as far as to call the admission of members of the opposition to parliament a “historic moment.”

Early statements from Brussels and Washington echoed the OSCE’s: things aren’t exactly democratic, they said, but there has been some progress that we want to see continue.

Even before the elections, Minsk, Brussels, and Washington were making efforts to improve relations, though the relationship was—and is—burdened by previous failed attempts at rapprochement: efforts to improve relations between 2008 and 2010 ended when Belarusian authorities dispersed a mass protest after the 2010 presidential elections and imprisoned its leaders.

It’s certainly hard for the West to turn a blind eye to Lukashenko’s authoritarianism, just as it’s hard for Lukashenko to ignore pressure from Moscow. Nobody wants to accidentally give Moscow a reason to ignite a second “Russian Spring.”

Each side is, as before, carefully assessing the other, afraid to do too much. Such a sluggish diplomatic process demands constant stimuli, the first of which came last year, with Minsk’s release of six political prisoners. Sanctions were soon suspended. Next came peaceful, repression-less presidential elections; the EU abolished its sanctions shortly thereafter. Then came this year’s parliamentary elections.

The path toward a closer relationship between the United States and Belarus is now more or less clear: Washington and Minsk will discuss lifting the sanctions and reinstating the ambassadors.

The EU, for its part, can offer Belarus several things: Minsk and Brussels have been negotiating a faciltation of the visa regime for the past three years, and now may be the time to hammer out any remaining technical issues (although a visa-free relationship is a long way off).

There is also the signing of a partnership agreement, which Brussels has negotiated with all the members of the Commonwealth of Independent States except Belarus and Turkmenistan. Minsk has called for negotiations on this agreement for a long time, and now may be the time for the EU to bring Belarus into the fold.

Things get trickier when it comes to money. Restrictions keeping the European Investment Bank (EIB) from working in Belarus and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) from working with the Belorussian state sector have already been lifted. Now it’s up to Minsk to propose projects that interest the EIB and the EBRD. Issues related to trade and investment will certainly be essential to any budding relationship between the EU and Belarus. Brussels can do several things on this front, including bringing Belarus back into the Global System of Trade Preferences and starting new investment forums.

Finally, the European Union can increase the scale of its development assistance to Belarus, which it doubled at the start of this year. But even in the best-case scenario, we’re talking about only a few hundred million euros spread out over many years. Minsk will be pleased, but the country’s economy will hardly feel the difference.

Seen from above, Brussels has a number of steps it can take, but none of them are game changers. After Lukashenko’s gesture in the parliamentary elections, European bureaucrats responsible for relations with Minsk will most likely pause to figure out what carrots the EU can offer Belarus next. They will have to choose carefully, however, because there are limits to partnership, and putting everything on the table at the same time would be imprudent.

This article was originally published by Carnegie Moscow Center